Causal Inference: What If Chapter 1-3

I was having dinner with a previous co-worker, who is a Machine Learning Engineer working on NLP stuff. He asked me, “So, what’s the difference between causal inference and association anyways? “

Good question. I thought to myself, and then asahmed to find our that I couldn’t come up with a well articulated answer on the spot after spending my past 2 years working on it. That’s why I started to read Causal Inference: What If, a practical introduction about causal inference focusing on epidemiology and social science. There are other books that I’m more familiar with the context, like Mostly Harmless Econometrics, (I decided it’s on my next list just because of the Author’s referece to Douglas Adams), but I decided to start with What if because 1) I’m very interested in social science topic 2) It’s easy to design randomized experiemnts in economics field, but hard for epidemiology and social science due to ethical reasons. Most avaiable data are observational, and I know making causal inference from observational data is a pain.

Chapter 1: Causation vs Association

The infereces with causation are essentially “What If” quesitons. What will happen in the counterfatual world, had all users been treated versus all users not been treated? We won’t know the “true” effect because we only have factual data, but we can make causal inference with factual data if we are willing to make certain assumptions.

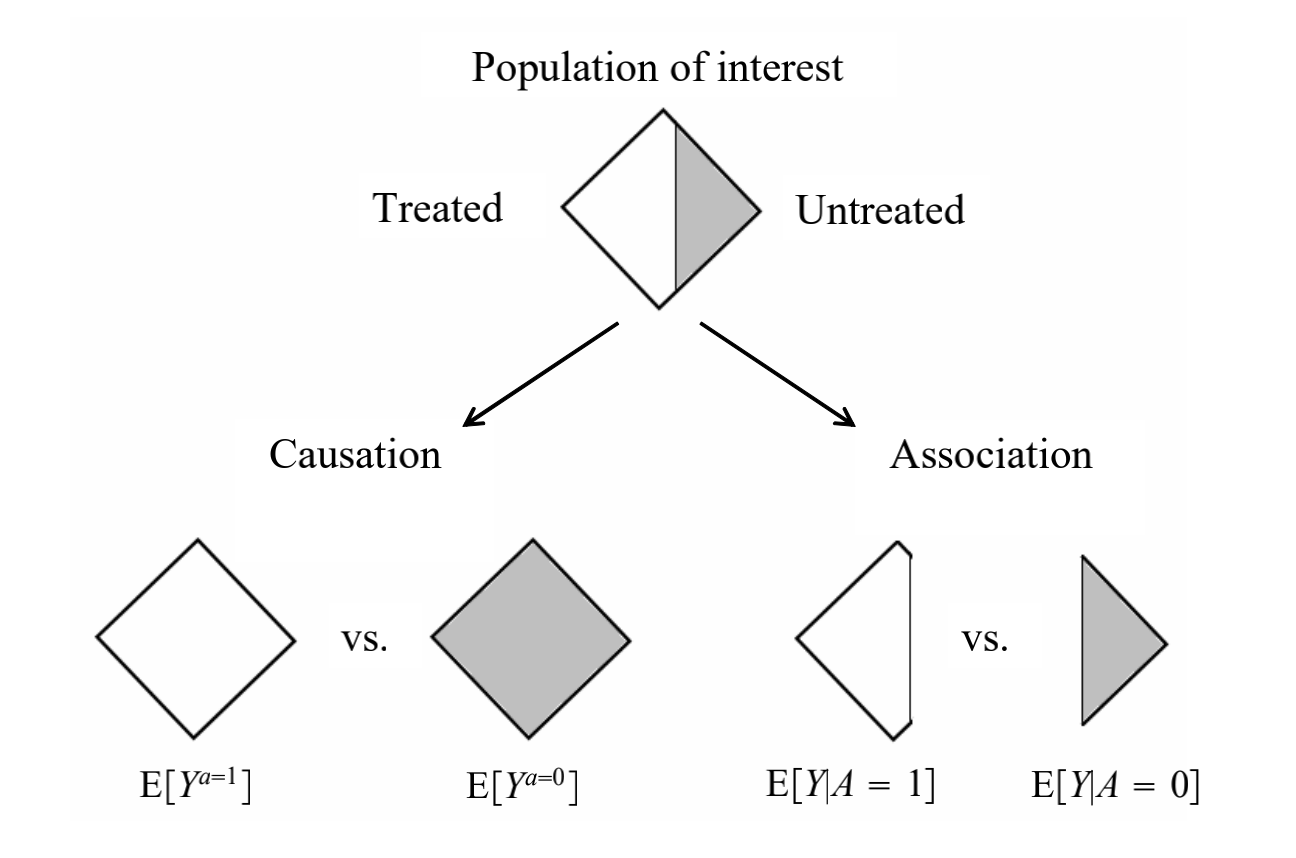

Causation is the risk in the same population under 2 different treatment values \(a = 1\) or \(a = 0\), while association is the risk in 2 subsets of population determined by the observed treatment value \(A = 1\) or \(A = 0\)

Chapter 2-3: Randomized Experiment and Observation Studies

Randomized experiment is useful because it gives us exchangibiity, meaning that the risk of death in treated users would have been the same as untreated users had them been treated. In math, it’s \(Y^a \perp\!\!\!\perp A\) for all values \(a\). Similarly, in a conditionally randomized experiment, \(Y^a \perp\!\!\!\perp A\) given \(L\) for all values \(a\). Under exchangebility, association is causation. Under either experiments, we can obtain the causal risk ratio by either standarization or inverse probability weighting. It means to create a pseudo-population by weighting each individual by the inverse of the conditional probability of receiving the treatment level.

In observational study, regarding the conditional randomization, it’s worth noted that it’s always an assumption and requires that expert knowledge is correct. Also, for us to effectively measure meaningful causal effects, one must define the treatment as specifically as possible to make sure the treatment is consistent, linkable to observed results, and meaningful if researchers need to propose intervention. It might sound obvious in A/B testing in industry, but totally not this case in social studies (what’s the defination of obesitiy? What does it mean by “keeping fit”?

Prediction vs Causal Inference Indentify individuals at high risk of mortality vs have effective and meaningful interventions to help reduce mortality rate for the population. By retreating into prediction from observational data, we avoid tackling questions that cannot be logically asked in randomized experiments, not even in principle. On the other hand, when causal inference is the ultimate goal, prediction may be unsatisfying.